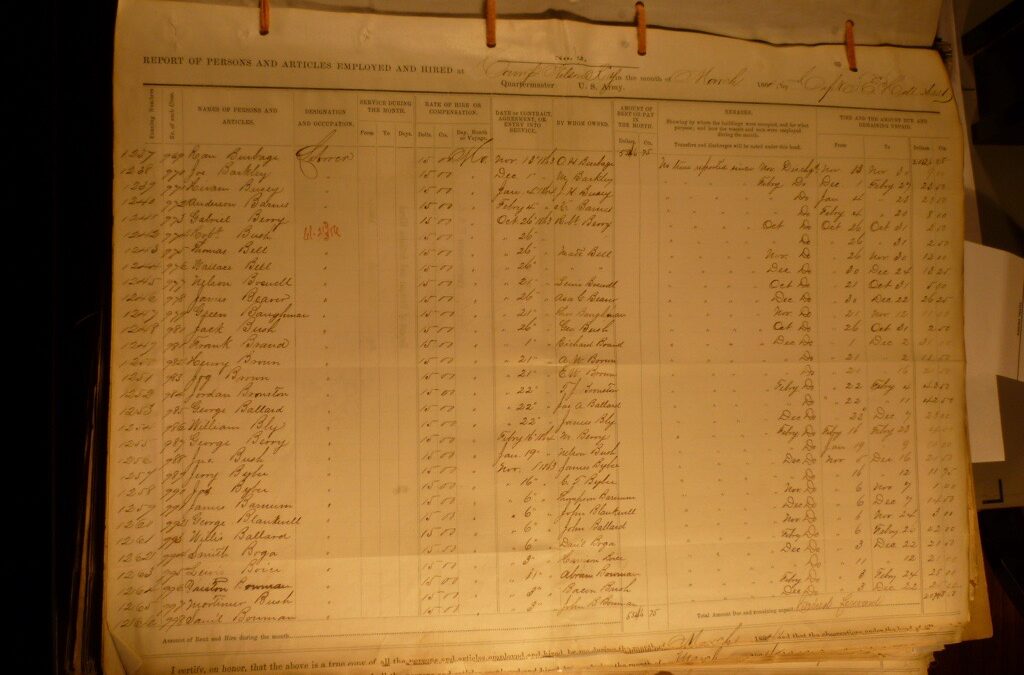

Figure 1: A U.S. Army impressment labor roll for enslaved workers at Camp Nelson, a military base in central Kentucky (NARA 1864).

By Cameron Boutin

The Civil War is an extensively documented conflict, with a wide range of reports, letters, diaries, and other records chronicling the big and small events. But the vast majority of these materials were written by white Americans—the voices of African Americans are much more limited, and those of people who were enslaved are even rarer. In U.S. history in general, generations of enslaved African Americans lived, worked, and died throughout the country with hardly any written record of their existence other than a bill of sale or note in a plantation account ledger. As a result, those wishing to learn more about the lives of enslaved people need to utilize various sources to try to piece together their stories. This is especially true during the Civil War years. In particular, one aspect of the enslaved experience during the wartime period that has received little attention is the military impressment of enslaved laborers.

Impressment was the policy of the U.S. and Confederate armies to seize food, animals, and other resources, including enslaved people, to support their operations in the field during the conflict. Enslaved people were forced to perform labor for the military, including building fortifications around key Confederate cities like Richmond and Petersburg in Virginia, and constructing roads to help move U.S. troops and supplies in Kentucky. Even after the U.S. government issued the Emancipation Proclamation—freeing enslaved individuals in Confederate territory—and began recruiting African Americans as soldiers, many enslaved people in Border States like Kentucky continued to be exploited by Federal forces. Both the U.S. and Confederate militaries paid for the impressed labor, but they provided the wages to the white slaveholders rather than the Black workers, who were also not given freedom for their service to the respective war efforts.

Few, if any, impressed African Americans left written accounts of their experiences as impressed laborers, but the documentation produced by the military to keep track of these individuals and the money owed to their slaveholders offer a wealth of information to present-day researchers. These impressment labor rolls recorded enslaved people’s names, perhaps for the first time in their lives. The records also generally listed their periods of service and the area of the country where they worked, along with the amount of compensation awarded to each enslaver (Figure 1). The impressment rolls provide a glimpse into enslaved peoples’ wartime experiences but taking that information and examining other types of governmental records can reveal more about their lives before, during, and after the Civil War.

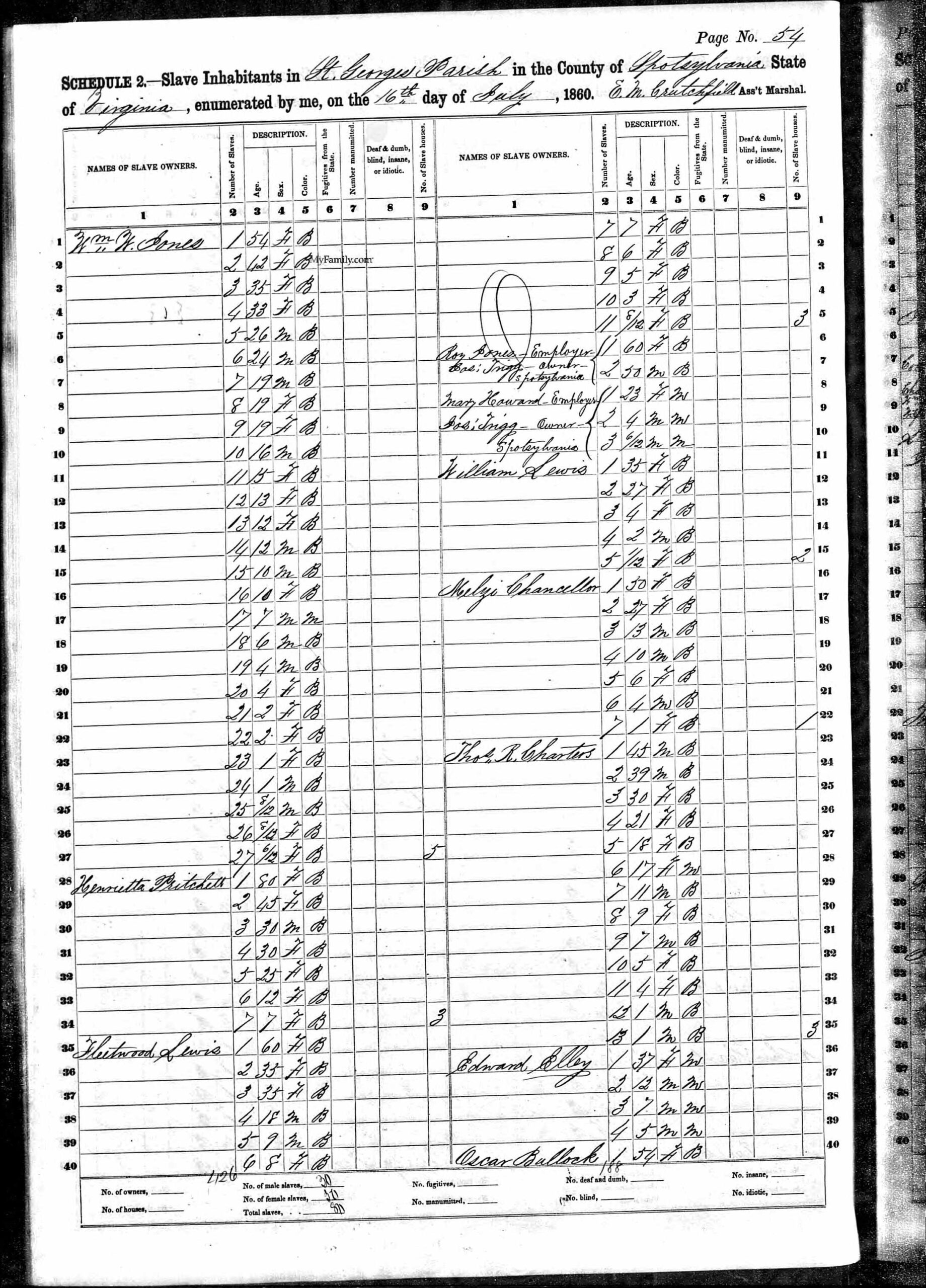

Figure 2: A page from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule for Spotsylvania County in Virginia (U.S. Slave Schedules 1860).

With the names of slaveholders and the likely county where they lived, researchers can use the 1860 U.S. Federal Population Census Slave Schedule (U.S. Slave Schedules) to determine the number of people they enslaved, along with their ages and genders. Was the impressed laborer part of a small, enslaved household of four to six people, or a large plantation with dozens? (Figure 2) An additional research avenue is taking the impressed laborers’ names and searching through the Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR) of the U.S. Army. Tens of thousands of formerly enslaved African Americans enlisted in the Federal military as U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) in the second half of the war, and their service records often included the names of their enslavers. Matching the names of the slaveholders from the impressment rolls can aid in confirming the identities of impressed laborers who eventually became USCT. One difficulty in locating impressed workers-turned-USCT is that the militaries’ labor rolls typically listed enslaved people with their enslavers’ last name. Many Black men retained their enslaver’s surname when they enlisted, while others chose to change it, making it difficult or even impossible to confirm the identities of these former impressed laborers.

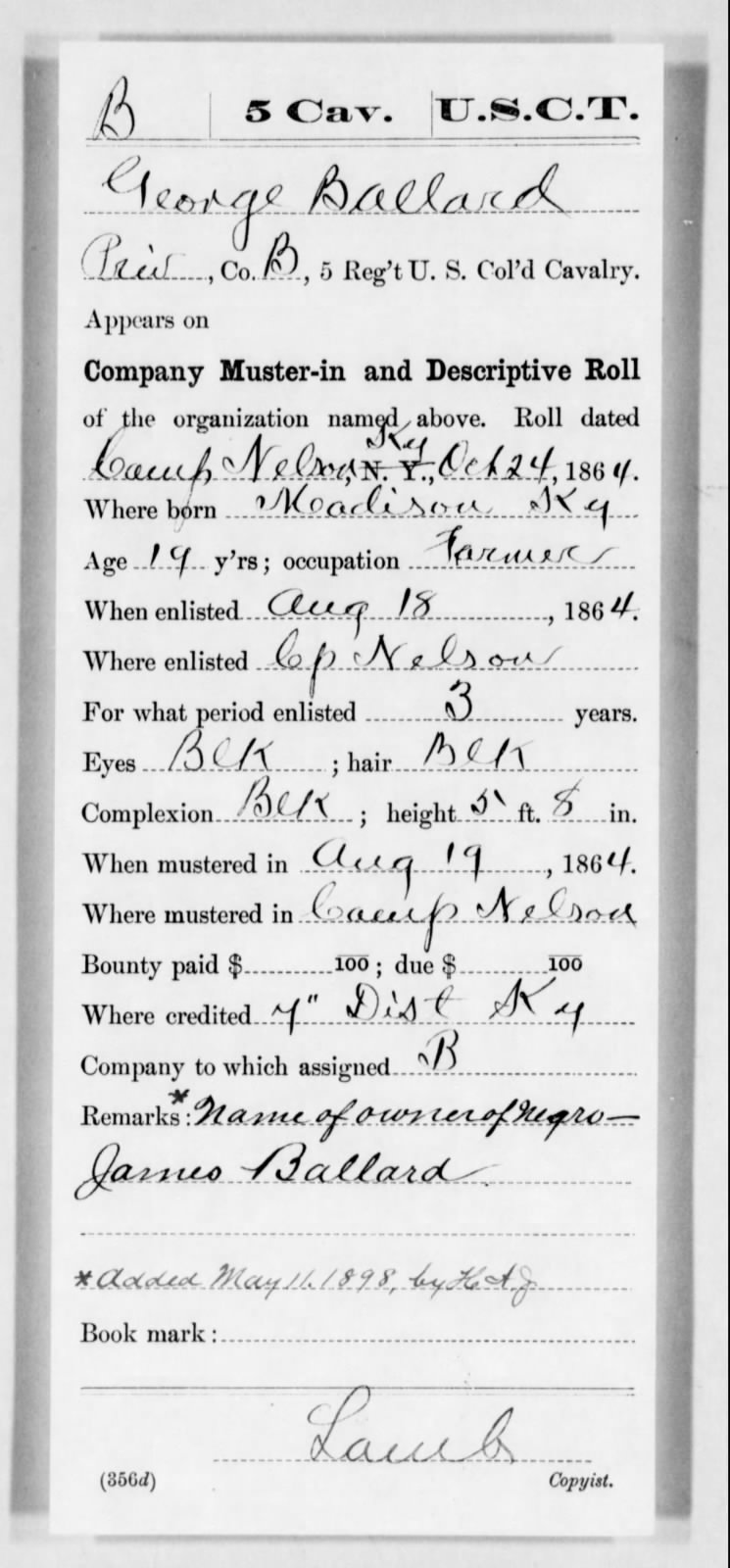

Figure 3: An enlistment page from the Compiled Military Service Record of George Ballard, a formerly impressed enslaved laborer who became a U.S. Colored Troop in Kentucky in 1864 (CMSR n.d.).

Military service records are filled with data related to individual soldiers, from basic background information like age and birthplace to bimonthly status reports tracking rank, duties, and involvement with the unit’s operations (Figure 3). A contemporary researcher looking through a service record can learn if a soldier was determined to be unfit for duty due to illness, was ever punished for a disciplinary problem, and the time and place of their discharge from the army, or alternatively, if they died during their service from combat or sickness. A formerly enslaved Black soldier may not have described his time in the military in a letter, diary, or memoir, but his service records tell their own story of his wartime experiences. Certainly, it is a limited and one-sided story, unable to reflect the personal reality of his life as a soldier, but it preserves crucial details that might have otherwise been lost to time.

Chronicling the experiences of enslaved people who were exploited as impressed laborers and/or enrolled in the military as USCT does not have to end with the close of the Civil War in 1865. Searching their names in the 1870 U.S. Census records can offer information on their postwar lives. Did they have a family? What part of the country were they living? What was their occupation? Did they own property? It can be possible to continue tracking these individuals through subsequent censuses, providing broad snapshots of their lives. Moreover, other types of military records remain invaluable sources of information, as the U.S. government awarded pensions to veterans and their widows throughout the late nineteenth century. Pension applications typically included details explaining the need for financial support, documenting the veteran’s service history, injuries, illnesses, and postwar hardships. These records offer insights into the long-term effects of military service on formerly enslaved soldiers and their families—struggles that may never have been written down elsewhere by the individuals themselves.

All of these diverse records—impressment labor rolls, census data, military service records, and pension applications—are preserved by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). They are publicly accessible, and many have been digitized for online access. Impressment rolls can be found in the National Archives digital catalog, while military service and pension records are available on the Fold3.com database, and census materials can be accessed through Ancestry.com (references to the different records are listed below). Learning about formerly enslaved people and their experiences during the Civil War era can be challenging, but examining these records and piecing together information helps bring their stories to light. Researchers can uncover the lives of individuals who may have left little to no written accounts of their own. Though incomplete, these documents offer crucial insights into their experiences and contribute to a deeper understanding of the Civil War as a whole.

References

Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR)

n.d. U.S. Civil War. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, https://www.fold3.com/, accessed March 2025.

National Records and Archives Administration (NARA)

1864 Impressment Labor Rolls of the U.S. Army Quartermaster at Camp Nelson. Record Group 92: Records of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. Washington, D.C. National Records and Archives Administration.

2020 Confederate Slave Payrolls Shed Light on Lives of 19th-Century African American Families. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/confederate-slave-payrolls-digitized, accessed March 2025.

U.S. Civil War Pensions Applications, 1861–1900

n.d. Pension Files of Veterans Who Seved Between 1861 and 1900. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, https://www.fold3.com/, accessed March 2025.

United States Federal Population Census (U.S. Census)

1870 Ninth Census of the United States, 1870. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, www.ancestry.com, accessed March 2025.

United States Federal Population Census – Slave Schedules (U.S. Slave Schedules)

1860 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules. Washington, D.C. National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic document, www.ancestry.com, accessed March 2025.