Featured Fragment –“Poppin’ Medicine Bottles”

By Katie Merli

Medicinal, pharmaceutical, and chemical bottles have a distinctive look to them, even today. Informative labels, child-proof closures, and even the well-known “Mr. Yuk” stickers from our youth set these bottles apart from other vessels. Physical modifications to bottles containing dangerous medicines separate them from their more innocent counterparts stashed away in the medicine cabinet. By the late 1800s, it was common for “chemical” or “poison” bottles to be brightly colored (generally cobalt blue or brilliant green), have embossed lettering/designs, or have the obvious labels of “POISON.” In case that wasn’t enough, some even sported the skull and crossbones to further get the point across. This was all done to ensure that the half-asleep person groping through their bathroom cabinet in the dark, as well as the illiterate, would understand that the contents inside were not meant for excessive or for any human to consume and should be used carefully (SHA 2021).

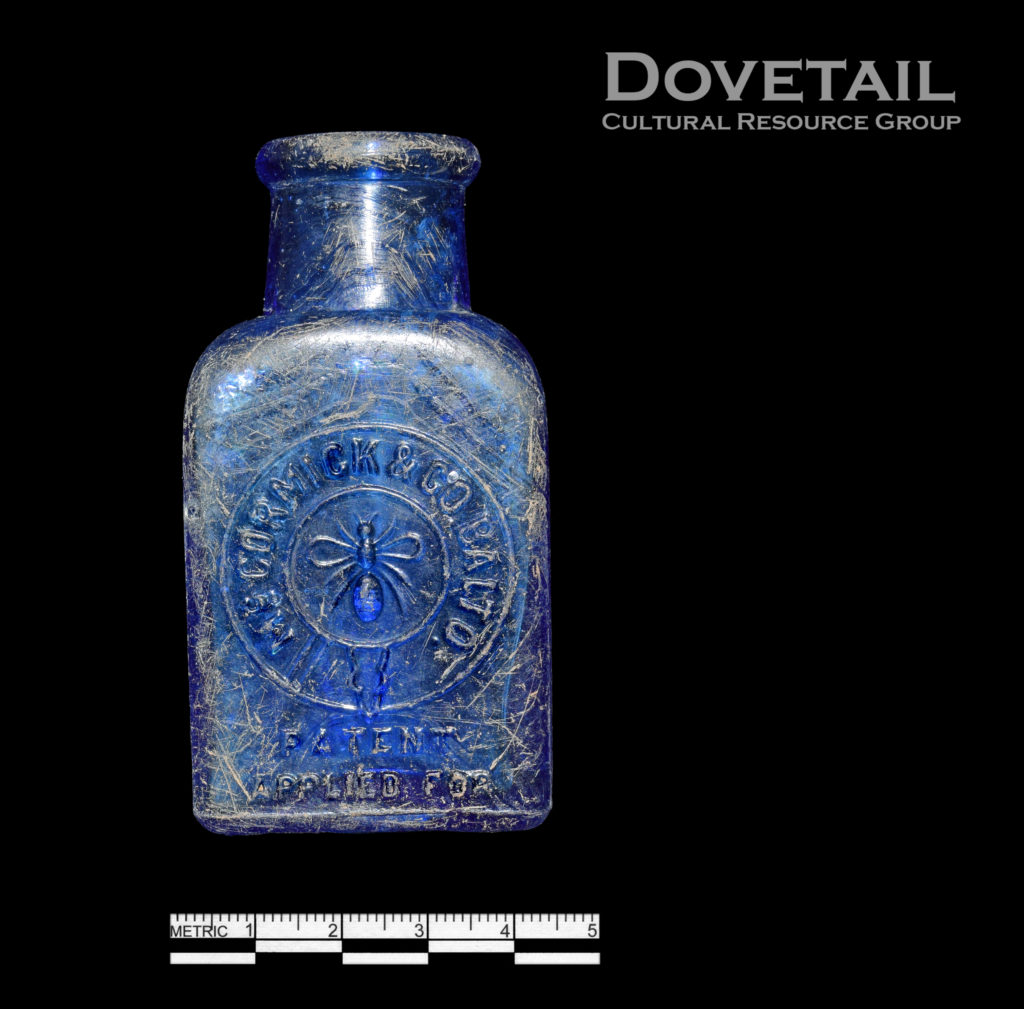

Two different examples of these “poison” bottles were recently found at the Heiskell-White archaeological site in downtown Fredericksburg, Virginia. One is a complete 3-inch tall, triangular shaped, cobalt blue bottle made by McCormick & Co. (yes, that McCormick). Their “Bee Brand” bottle (circa 1890s–1902) (Photo 1), with its bright color and noticeable shape, would have most likely contained laudanum (Figure 1). A tincture of opium and alcohol was used in the treatment of pain, cough, diarrhea, and a variety of other medical debilitations since the eighteenth century; this medication was relatively widespread and readily available. Less aggressive versions of laudanum are still prescribed today.

Photo 1: McCormick & Co. “Bee Bottle” Found During Excavations at the Heiskell-White Site in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

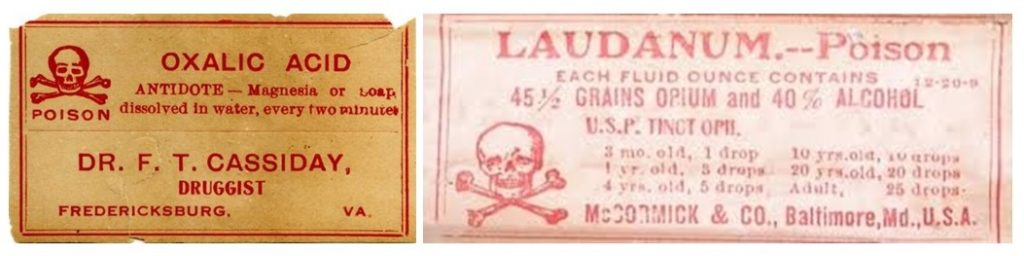

Figure 1: On Left: Oxalic Acid Label From Cassiday’s Drugstore, Downtown Fredericksburg On Right: McCormick & Co. Laudanum Bottle Label (www.dawnfarm.org 2014).

The second bottle found on the site has a small cylindrical shape with embossed lettering. Only a light aqua color, it is a less obvious example of a poison/medicinal bottle (Photo 2). “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup,” made by Curtis & Perkins, was given to infants and children to help sooth teething, fussing, diarrhea, etc.; the primary ingredients being morphine and alcohol (Figure 2). With alarming dose recommendations (roughly 6 to 20 times as much as laudanum depending on the child’s age), it is no wonder that this syrup quickly became known as a “baby killer” medicine as one teaspoon contained enough morphine to kill the average child (Museum of Healthcare 2017). By 1911, the United States passed the Pure Food and Drug act, forcing Curtis & Perkins to remove morphine from their recipe and “soothing” from their label. With this change, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup was able to be produced and used through the 1930s (Museum of Healthcare 2017).

Photo 2: Curtis & Perkins Bottle for Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup Found During Excavations at the Heiskell-White Site in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Figure 2: Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup Trade Card (Museum of Healthcare 1887).

By the 1890s, various drug advertisements, especially for children’s medicine, began to advertise their “harmless” nature as a means to avoid association with these dangerous alternatives (Sears, Robuck & Co. 1897).

Both of these medicines were easily obtained and led many people, young and old, to become addicted to the substances. Small artifacts such as these, especially when found intact, give archaeologists a sense of what the people of the time were turning to for their day to day maladies, and remind us that maybe we don’t have it quite as bad today.

Any distributions of blog content, including text or images, should reference this blog in full citation. Data contained herein is the property of Dovetail Cultural Resource Group and its affiliates.

References:

Dawnfarm.org

2014 Opiates and Medicine: Where are we, America? Electronic document, https://www.dawnfarm.org/wp-content/uploads/OpiatesAndMedicineHANDOUTS_09-23-20141.pdf, accessed February 2021.

Museum of Healthcare

2017 Mrs. Winslows Soothing Syrup: The Baby Killer https://museumofhealthcare.wordpress.com/2017/07/28/mrs-winslows-soothing-syrup-the-baby-killer/, accessed February 2021.

Sears, Robuck & Co.

2007 1897 Sears Robuck & Co. Catalog, Page 39, accessed February 2021.

Society of Historical Archaeology

2021 Poison and Chemical Bottle Styles https://sha.org/bottle/medicinal.htm#Chemicals%20and%20Poisons, accessed February 2021.