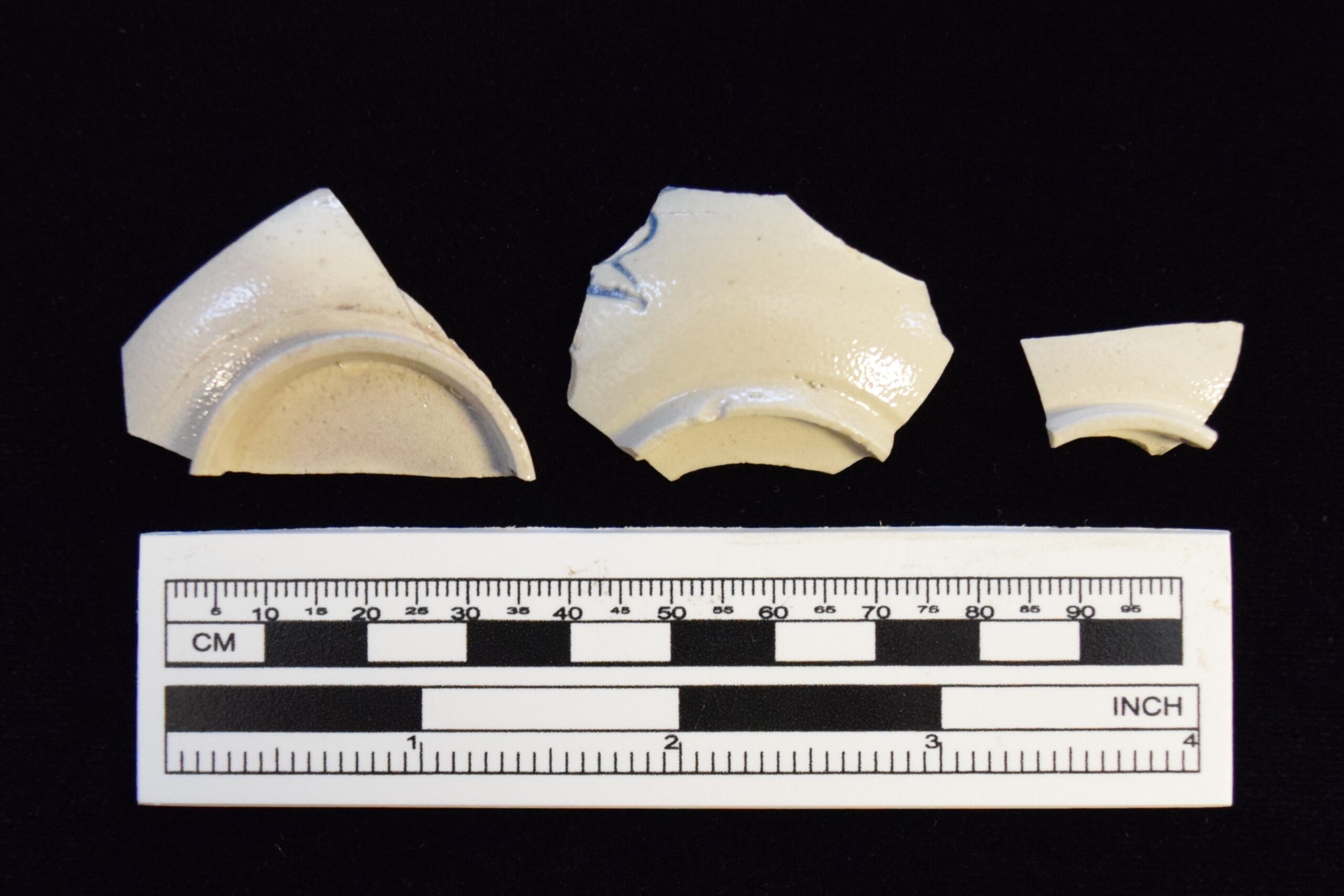

Photo 1: Scratch Blue Teaware Fragments Recovered from the Top of a Well.

By Colleen Betti

Over the past month, archaeologists from Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), a Mead & Hunt company, have been working on a data recovery project in Sussex County, Delaware. Data recovery excavations occur ahead of site impacts to recover the artifacts from a site as well as document and excavate features—the nonportable evidence of past lives such as foundations, wells, and hearths. The site appears to have been a domestic site occupied in the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century. Remains of a well and pits with domestic refuse were found. Although we are still in the early stages of site analysis, it appears that the occupants of the site were of a lower socio-economic status, possibly enslaved or poor tenant farmers. Ceramics were the most common artifacts found at the site, after clam and oyster shell. While redwares, especially cheaper domestically produced redwares, dominated the ceramic assemblage, there were also approximately 30 scratch blue ceramic sherds representing multiple vessels. White salt-glazed stoneware, and the scratch blue variant in particular, were the only stoneware found during the data recovery excavations. There were almost double the number of scratch blue sherds compared to tin-glazed earthenware sherds and only three Chinese porcelain fragments. No other imported stonewares like Westerwald or Fulham were found. Despite their low socioeconomic status, why would the residents of Walden have scratch blue vessels in larger numbers than tin enamel wares or other imported stonewares like Westerwald?

Photo 2: Interior of the Scratch Blue Teacup Rims from the Well. Note the three lines on the left three pieces and two on the fragment on the right, indicating they belong to different vessels. Additionally, one of the pieces with three lines has a band on the exterior (see Photo 1) indicating it also belongs to a different cup.

Scratch blue is a variation of the popular white salt-glazed stoneware. White salt-glazed stoneware, which began being manufactured in England in the late seventeenth century, was most popular between 1720 and 1770. It was the most widely used tableware and teaware in England from 1720 until creamware was introduced in the 1760s, and that tradition carried over to the Americas. Scratch blue, made by incising lines in the surface of the vessel before it was fired and infilling them with cobalt blue oxide, began being produced in 1742 and was made until 1778. It dominated the white salt-glazed stoneware market between 1742 and 1750. A “debased” version where the cobalt blue oxide was less carefully applied and spread outside of the incised lines, began being produced in 1760 to compete with another style/form called Westerwald and was made through the 1790s. Scratch blue vessel forms included teaware, especially cups and saucers, chamber pots, pitchers, mugs, and punch bowls (Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab 2015; Noel Hume 1969). Teacups and saucers are the most common scratch blue vessel forms found in what is now the United States (Skerry and Hood 2009). All the scratch blue from the data recovery site appears to be teaware, and it is all the original neat version, not debased. Sherds from at least three separate teacups were found in the well along with at least two saucers. An undecorated white salt-glazed stoneware lid was also found in the plow zone, suggesting that the site occupants may have only purchased fancier scratch blue vessels as cups and saucers, not the entire tea set.

Photo 3: Scratch Blue Saucer Bases from the Well.

Photo 4: White Salt-Glazed Stoneware Lid, Possibly from a Teapot.

So, what made scratch blue so popular? And why was it the most common ware type at the data recovery site, outside of redware? In the mid-eighteenth century, white salt-glazed stoneware filled a gap in the market. It was more affordable than imported Chinese porcelain, sturdier than the soft-pasted tin enameled wares, and more aesthetically pleasing for display than plain white salt-glazed stoneware or coarse earthenwares (McMahon 1984). While slipwares, which are coarse earthenwares decorated with slip, a thin colored clay, often in linear patterns, were affordable and common in the eighteenth century (and many were found at the data recovery site), they were thicker, clunkier, and decorated in muted earthtones and often served more utilitarian functions. Scratch blue imitated the designs, colorways, and delicate nature of Chinese porcelain without the hefty price tag. It replaced tin-enameled wares, which had served a similar function, but were more fragile, since tin-enamel glazes are more prone to flaking off the vessel body (McMahon 1984). Despite their lower socio-economic status, the residents of the data recovery site wanted to participate in the growing culture of the tea ceremony. Throughout the eighteenth century in England, and in the English colonies like Delaware, tea drinking became a crucial part of social life and manners with a set ceremony, and the material goods linked with tea drinking, were a way to show status (Roth 1961). An entire Chinese porcelain set was likely outside of their budget, so individual scratch blue pieces served to elevate a more affordable, white salt-glazed stoneware tea set. No matter what time period, people of all socioeconomic statuses participate in changes in styles and the latest trends. The purchasing of scratch blue teawares rather than Chinese porcelain is not so unlike modern Americans buying the recently released $80 Walmart Wirkin Bag, an imitation of the much more expensive Hermes Birkin Bag, for those that cannot spend $30,000 or more for a handbag.

References

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab

2015 Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland. Electronic document, https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/, accessed February 2025.

McMahon, Dawn Fallon

1984 Requa Site Scratch Blue White Saltglaze Stoneware. The Bulletin and Journal of Archaeology for New York State 89:30–43.

Noël Hume, Ivor

1969 A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Roth, Rodris

1961 Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America: Its Etiquette and Equipage. United States National Museum Bulletin 225. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Skerry, Janine E., and Suzanne Findlen Hood

2010 Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America. Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, Virginia.