By Danae Peckler

Tobacco barns may still be something of a common sight in central and southern Virginia, but their days are increasingly numbered. Listed as one of Preservation Virginia’s Most Endangered Historic Properties in 2009, many are being reclaimed by the rural landscape that they once defined. Since 2009, Preservation Virginia has documented and repaired some of these iconic buildings to preserve the history and heritage of tobacco faming in Virginia and parts of North Carolina. This work has involved recording hundreds of flue-cured tobacco barns, named for the method used to process the crop, identifying unique examples like the Fitzgerald-Hankins Tobacco Barn in Pittsylvania County, Virginia (Photo 1 and Photo 2).

Photo 1: View of Fitzgerald-Hankins Barn Looking West Taken in 2010 (Courtesy of Preservation Virginia).

Photo 2: Detail of Northeast Corner Showing Tie Plates at Eaves of Fitzgerald-Hankins Barn (Peckler 2020).

To better understand the history of this barn, Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail) joined with Sonja Ingram, Tobacco Barn Project Manager, Professor Michael Spencer, Chair of University of Mary Washington’s (UMW) Historic Preservation Department, and Tessa Honeycutt, a UMW preservation graduate and Preservation Virginia intern, to research and document this resource in the summer of 2020. The building had been vacant since the 1960s, but became ruinous after a series of storms in 2019. This joint documentation occurred just prior to its demolition in September 2020.

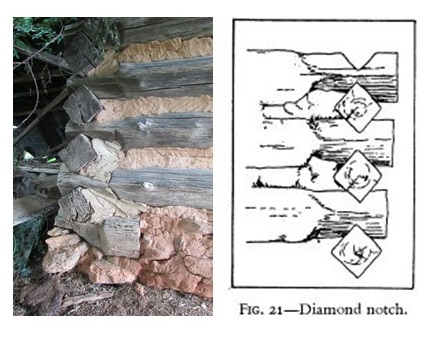

The Fitzgerald-Hankins barn was a 20-x-20-foot, single pen, unhewn, log building—but do not mistake simple for inferior; it likely stood for more than 150 years! This form of tobacco barn, or “tobacco house” as they were called from the eighteenth to the late-nineteenth century, were built from the late 1700s into the early 1900s, yet the Fitzgerald-Hankins barn stands apart for its diamond-notched corners (Giese 2004:3) (Photo 3).

Photo 3: At Left, Image of Diamond-Notching at Southeast Corner of Fitzgerald-Hankins Barn (Peckler 2020); At Right, Sketch of Diamond Notching (Kniffen and Glassie 1966:55).

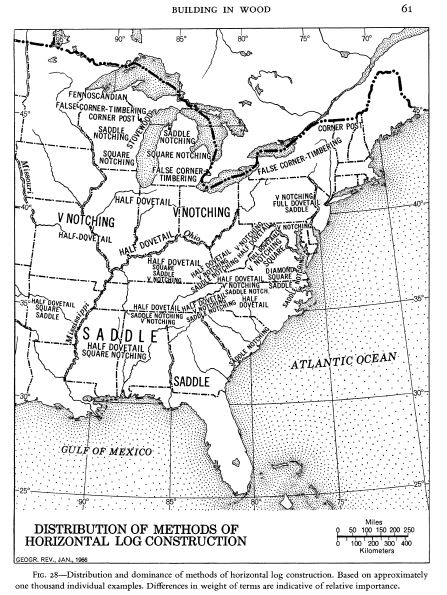

Figure 1: Map Depicting “Distribution and dominance of methods of horizontal log construction. Based on approximately one thousand individual examples. Differences in weight of terms are indicative of relative importance” of Corner Notching in Eastern United States (Kniffen and Glassie 1966:61).

One of a few distinctly “American” forms of corner timbering, diamond-notching is rare with relatively few survivors of this type remaining across the country. In fact, just six of 230+ historic tobacco barns surveyed by Preservation Virginia in Pittsylvania County were built using this method (Ingram 2015). Cultural geographers and architectural historians have noted the relative scarcity of this type and tied it to Swedish traditions, though current research more appropriately traces the four-sided diamond notch as an evolution of the Finnish six-sided diamond notch (Jordan et al. 1987; Kniffen and Glassie 1966; Personal Communication, Douglass Reed 2020). Regardless of the diamond notch’s European roots, the four-sided version emerged in the Mid-Atlantic region of the country with the highest concentration of this type of log buildings documented in south-central Virginia (Jordan et al. 1987; Kniffen and Glassie 1966) (Figure 1). Scattered examples of diamond-notched buildings identified in central Tennessee, eastern West Virginia, and central and eastern North Carolina largely date from the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries (Cooper 1999; De Graauw 2020; Gavin 1997). However, little data has been compiled on this type of log construction in recent decades.

A handful of diamond-notched tobacco barns in surrounding counties have been identified from materials at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources archives, but six extant examples in one county is an outlier. Why do so many survive in Pittsylvania County? Did the people there maintain the diamond-notching tradition longer than in other parts of the state or even the country?

Oral history from property owner, James Hankins, states that the logs of the barn were cut by an enslaved woman—something he heard from the grandchildren of Thomas Fitzgerald (1818–1892). The son of a wealthy family with large land holdings, Thomas was gifted a 640-acre tract of land, nearly twice the size of the County’s average farm, from his father in 1846. Buying and inheriting additional land over time, Thomas came to control more than 1,700 acres that he managed through tenants, overseers, enslaved laborers, and sharecroppers. On his home farm, Fitzgerald reported owning 27 enslaved people in 1860, many of whom may have resided in one of four slave dwellings there—far less than the 300 people held in bondage by the county’s largest slaveowner—and produced substantially less tobacco than his contemporaries (U.S. Agricultural Census n.d.; U.S. Slave Schedule 1860). Keeping with a diversified farming strategy, Fitzgerald turned to milling in the decade after the Civil War, operating a grist and flour mill in 1870 (U.S. Manufacturing Census 1870).

Although a specific construction date for the Fitzgerald-Hankins barn could not be determined prior to its demolition, its diamond-notch construction suggests an early-nineteenth-century date. Given its longevity, it is no surprise that the barn has been modified on multiple occasions to suit market preferences and changes in tobacco technology. While these alterations obscure its past, they are also the reason that it survived into the twenty-first century prior to its September 2020 demolition.

And where there were once many, now there are five.

Any distributions of blog content, including text or images, should reference this blog in full citation. Data contained herein is the property of Dovetail Cultural Resource Group and its affiliates.

References:

Cooper, Patricia Irvin

1999 Migration and Log Building in Eastern North Carolina, Material Culture 31(2):27–54.

De Graauw, Kristen

2020 Historic Timbers Project. Electronic document, https://historictimbersdendro.wee

bly.com/?fbclid=IwAR2BEMBe5sYPz0Uv0fbhdhdeB7ruTgQqPAktKcX3Vwx7xiUNzdTDxOW45PA, accessed August 2020.

Gavin, Michael

1997 The Diamond Notch in Middle Tennessee. Material Culture 29(1):13–23.

Giese, Ronald L.

2004 Historic Virginia Tobacco Houses. Middleton, Wisconsin. Copy on file at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources Archives, Richmond.

Ingram, Sonja

2015 Pittsylvania Tobacco Barn Survey, Final Report. July 2015. Preservation Virginia. Copy on file at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources Archives, Richmond.

Jordan, Terry G., Matti Kaups, and Richard M. Lieffort

1987 Diamond Notching in America and Europe. Pennsylvania Folklife 36(2):70–78.

Kniffen, Fred, and Henry Glassie

1966 Building in Wood in the Eastern United Station: A Time-Place Perspective, Geographical Review 56(1):40–66.

U.S. Agricultural Census

n.d. Non-Population Census Schedules, Pittsylvania County, Virginia, 1850–1880. Electronic database, www.ancestry.com, accessed July 2020.

U.S. Manufacturing Census

1870 Non-Population Census Schedules, Pittsylvania County, Virginia. Electronic database, www.ancestry.com, accessed July 2020.

U.S. Slave Schedule

1860 Slave Schedule, Pittsylvania County, Virginia. Electronic database, www.ance

stry.com, accessed July 2020.