Civil War battlefields are quite common across Central Virginia. With population growth and associated developments in the region, local groups are striving to protect former battlefield grounds for future generations. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), a Mead & Hunt company, is very proud to assist these groups with their preservation goals to help research the history of these important areas and perform archaeological studies to learn about the artifacts that soldiers may have left behind.

Historical interpretations of battlefields often describe the regiments were involved, the location of earthworks and battle lines, and the outcome of the engagement. More recently, scholars are assuring that the narratives go beyond the battle to include the experiences of the soldiers who fought in the war and the citizens who were deeply impacted by war-related occupation. Archaeological research brings in another dimension to the story as we study what was physically discarded or left behind. Not only do artifacts such as musket balls and bullets tell us crucial information about Civil War weaponry and combat, but the items scattered across battlefields and camps reveal information about soldiers’ daily activities and lives. For this blog, I wanted to talk about an artifact type that many would consider commonplace but which tells a key side of battlefield logistics and daily life in the 1860s—the horseshoe.

Horses and mules were critical for the operations of Civil War armies. Horses supplied necessary mobility for men and artillery, while mules were utilized as draft animals, pulling the wagons and carrying the supplies that supported thousands of soldiers on the move. A sobering statistic is that deaths were higher for horses and mules than men; it is estimated that of the 3 million horses and mules that served during the Civil War, more than 1.2 million died compared to around 620,000 soldiers (Bainbridge 2021; Reichard and Grabowski 2017).

Horseshoes were vital to the health of horses. They served a number of functions: added traction, improved balance, and strengthened and protected hooves for medical reasons. Horses and mules in the Civil War-period would have encountered varied terrains, heavy workloads, and long-distance traveling. Good shoes were essential and with heavy use, these animals needed to be reshod often (Bainbridge 2021; Horse and Country TV 2024).

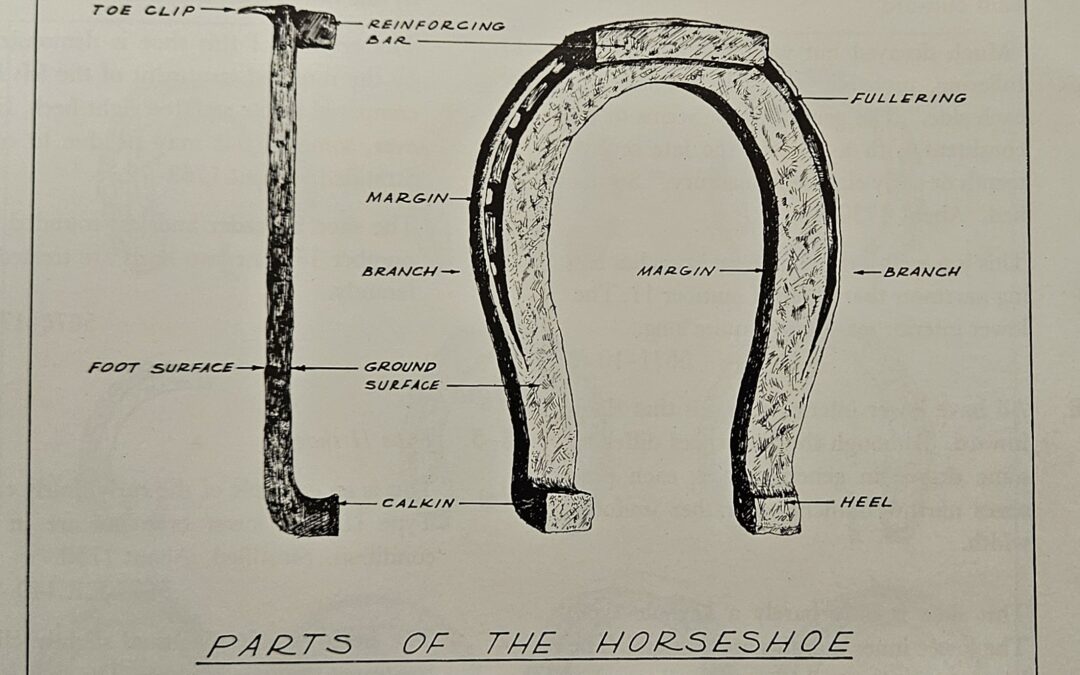

Horseshoes are artifacts that have not changed greatly since the seventeenth century. Their size and shape are dependent on the animal and the style or skill of the blacksmith or farrier. Figure 1 shows the parts of the horseshoe. Nineteenth-century horseshoes typically have calkins (a type of metal cleat), heels that are slightly curved outward, and toe clips or reinforcing bars (Bainbridge 2021; Chappell 1973:102, 105, 106, and 109).

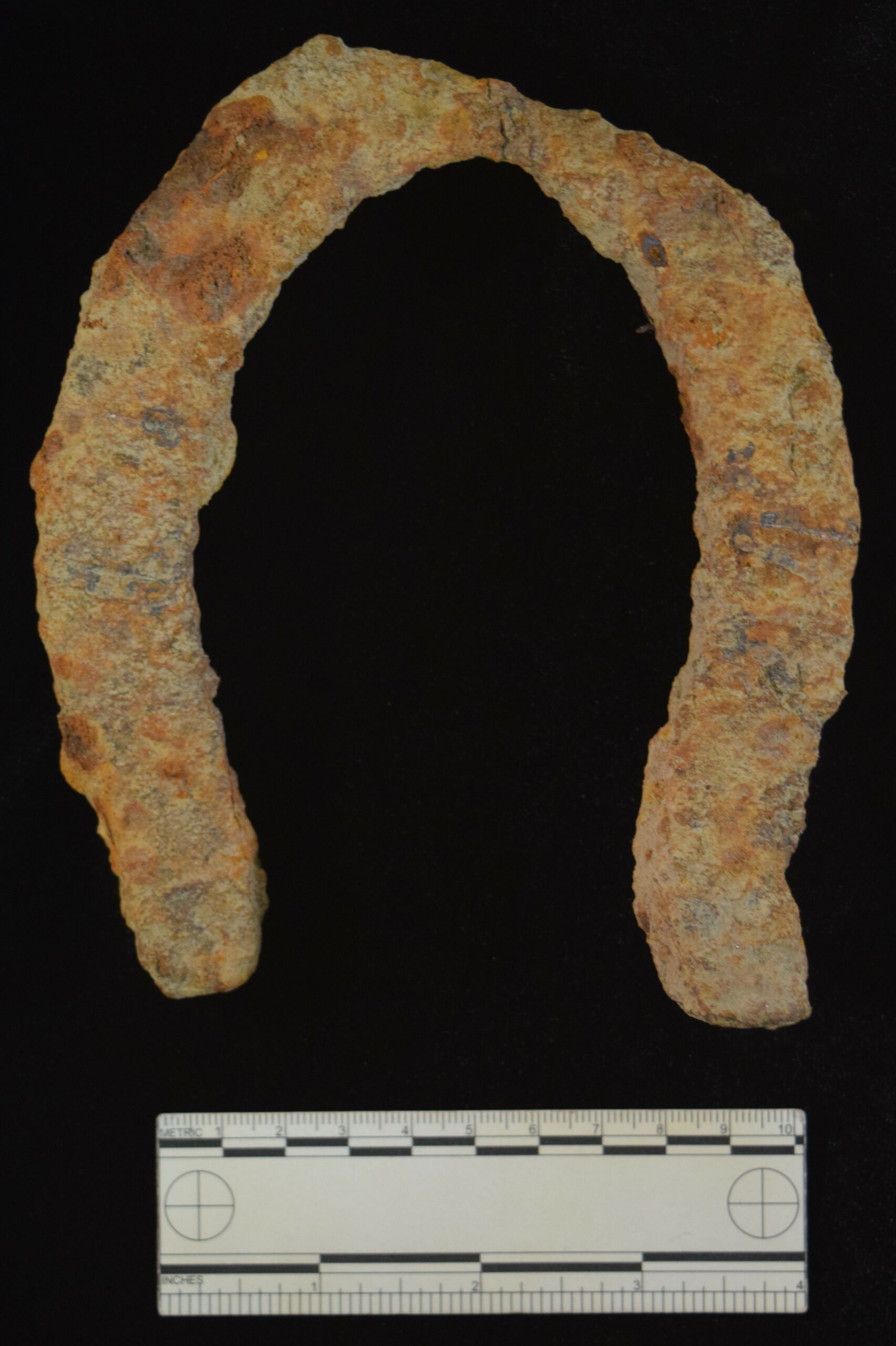

Photo 1: Examples of Mule Shoes. Photo by Dovetail.

Horseshoes were hand-made until Henry Burden’s first patent in 1835 that included the use of three separate machines for manufacturing. In 1857, he had perfected the ability of one machine to cut, bend, and forge a shoe. At its peak, Henry Burden and Sons could produce approximately 2,600 horseshoes per hour of various sizes for riding horses, mules, and draft horses. With his factories located in Troy, New York, the United States (U.S.) Army benefited greatly from his factories. These horseshoes were so important that the Confederacy unsuccessfully sent spies to learn how to replicate his horseshoe-making machines and sent raiding parties to block or capture their shipments from railroads or wagon trains (Bainbridge 2021).

When conducting archaeological surveys at battlefields in Central Virginia, horseshoes are one of the most prevalent types of artifacts that are discovered. On one such site recently surveyed by Dovetail, 29 shoes were recovered. In-depth analysis and further research on these horseshoes are revealing the types of horses and draft animals that were present and how they were treated in the battlefield environment.

While the vast majority of horseshoes appear to have been specifically for horses, the grouping from the recent Dovetail survey contained four shoes that were different. Three complete mule shoes and one mule/pony shoe fragment were recovered. Mule shoes have a more-rounded toe shape with straighter sides than those specifically for horses. These examples were also of a narrower width of only 4.0 to 4.5 inches and a length of 4.5, 5.75, and 6.0 inches. The other fragmented shoe still maintained its reinforcing bar, but its calkin/heel was fragmented or worn off. It was also about 4.0 inches wide and approximately 4.5 inches long. No oxen shoes were identified (Blumenstein 1968).

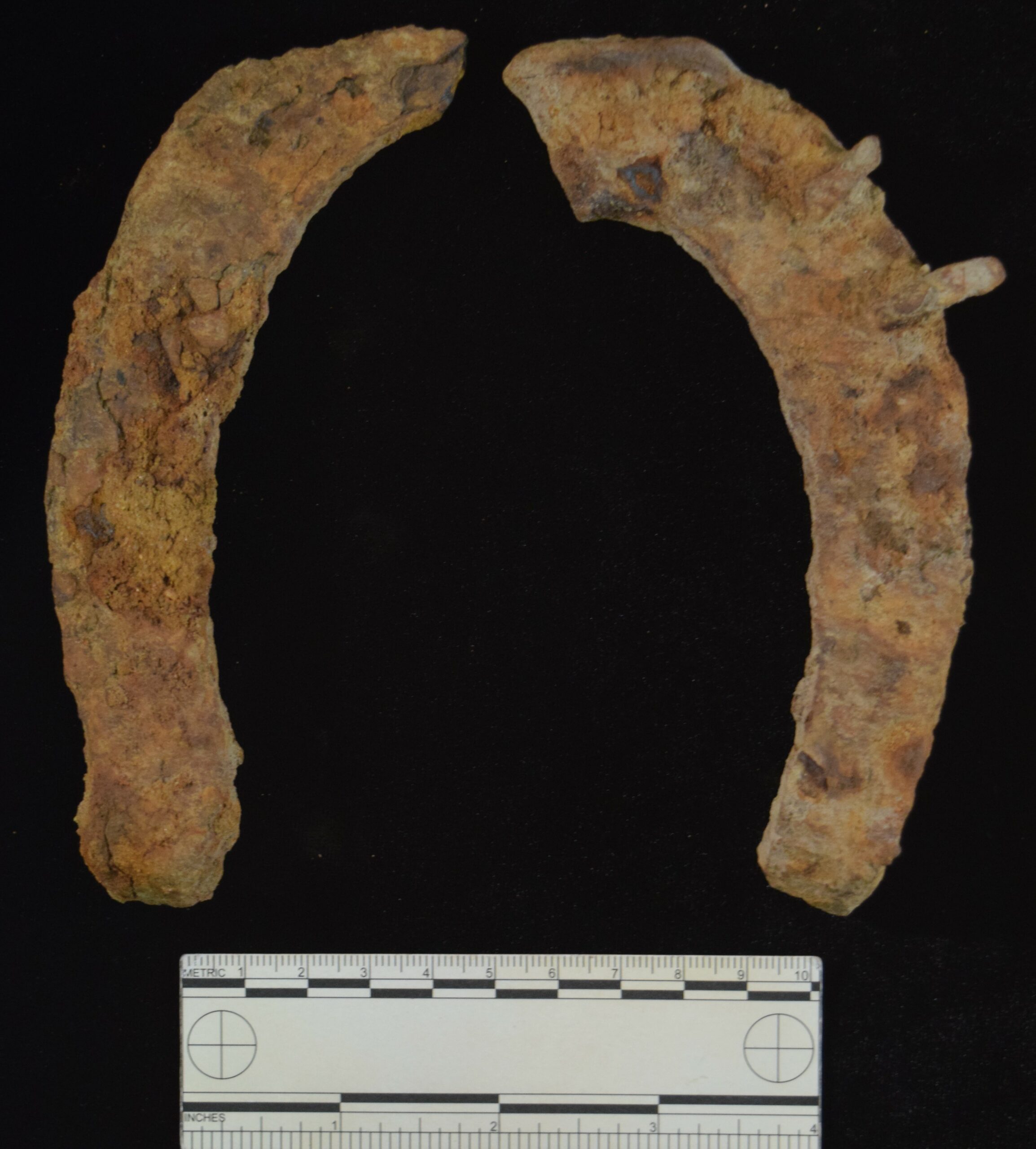

Photo 2: Complete Horseshoe. Photo by Dovetail.

Of the horseshoes found, only two were complete. Neither exhibited a reinforcing bar, and they both measured 5.75 inches in length. One example exhibited a large diagonal wear pattern across the toe while the other was twisted. These shoes were quite sizeable in length and probably were utilized on some of the bigger horses. The remaining horseshoes were fragmentary in nature. Most appear to be horseshoe fragments, but several might be mule shoe fragments. Interestingly, 23 shoe fragments were broken at almost the exact same spot—at the top approximately halfway across the toe. Only a few shoes still had the corresponding nails still in the horseshoe. Interestingly, many shoe fragments could be defined as to which side of the hoof they belonged; eight shoes were from the left side, eight sides were from the right side, and seven fragments could not be determined. The majority of the horseshoe fragments measured between approximately 4.0 and 6.0 inches in length, corresponding to the wide variety of sizes in horses and draft animals used by both the Confederate and U.S. armies.

Photo 3: Horseshoe Fragments. Photo by Dovetail.

Overall, all shoes showed extreme wear use. Even with their rusted surfaces, every shoe exhibited extremely worn surfaces, particularly in the heel/calkin and toe areas. The number of broken shoes also suggests that many horses might have worn shoes much longer than recommended. In fact, I would not be surprised if many horses had their shoe actually fragmented on their hooves while still being worn.

The archaeological evidence suggests that while Civil War soldiers heavily utilized horses, they often did not (or could not) care properly for their animals when it came to horseshoes. Horses and mules were vital to the logistics and movements of both the Confederate and U.S. armies, but the issues with the repair of their shoes was detrimental. Veterinary medicine did not truly exist during the Civil War period, and soldiers did the best that they could under the circumstances to take care of the animals. In fact, Confederate cavalrymen were responsible to provide their own mount, care for it, and find a replacement if it died. Even the U.S. Army’s Quartermaster Department was upset at the unnecessary animal casualties due to neglect (Reichard and Grabowski 2017).

Would I say that a horseshoe was good luck if I was a horse during the Civil War? I think not!

References

Bainbridge, David A.

2021 How Horseshoes Helped Win the Civil War. American Farriers Journal. Electronic document, https://www.americanfarriers.com/articles/12850-how-horseshoes-helped-win-the-civil-war, accessed July 2024.

Blumenstein, Lynn

1968 Wishbook 1865: Relic Identification for the Civil War Era. Old Time Bottle Publishing Company. Salem, Oregon.

Chappell, Edward

1973 A Study of Horseshoes in the Department of Archaeology, Colonial Williamsburg. In Five Artifact Studies, edited by Audrey Noel Hume, Merry W. Abbitt, Robert H. McNulty, Isabel Davies, and Edward Chapell, pp. 100-116. Colonial Williamsburg Occasional Papers in Archaeology. Volume I, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Horse and Country TV

2024 Do Horses Need Shoes? The Pros and Cons of Shoeing. Electronic document, https://horseandcountry.tv/en-us/why-do-horses-need-shoes-horse-shoeing-guide/#why-do-horses-wear-shoes, accessed July 2024.

Reichard, Katie, and Amelia Grabowski

2017 “Every Man His Own Horse Doctor”. National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Electronic document, https://www.civilwarmed.org/animal/, accessed July 2024.