By Colleen Betti

When you think about artifacts associated with schoolhouses, slate pencils, writing slates, ink bottles, and marbles come to mind. But when I excavated at three 1880s–1950s African American schoolhouse sites in Gloucester County, Virginia for my dissertation, what I was not expecting to find were numerous jelly juice jars. However, jelly juice jars and other drinking vessels from the Woodville (44GL0523), Bethel (44GL0273), and Glenns/Dragon (44GL0550) School sites provide key evidence for the implementation of public health campaigns as well as racial discrimination.

Jelly juice jars were vessels in which jelly and other condiments were sold and then converted into drinking glasses once empty. They did not have a string rim at the top (a raised line around the opening), which made them ideal for their secondary use as drinking vessels. Beginning in the 1870s and 1880s, jelly jars were made in a variety of shapes, but after World War I, they were mostly produced in a tumbler shape (Bowditch 1986). Many brands made their glasses decorative. In the early twentieth century, the most-common molded design was bands of knurling (decorative embossed bands) around the rim in different patterns (Figure 1).

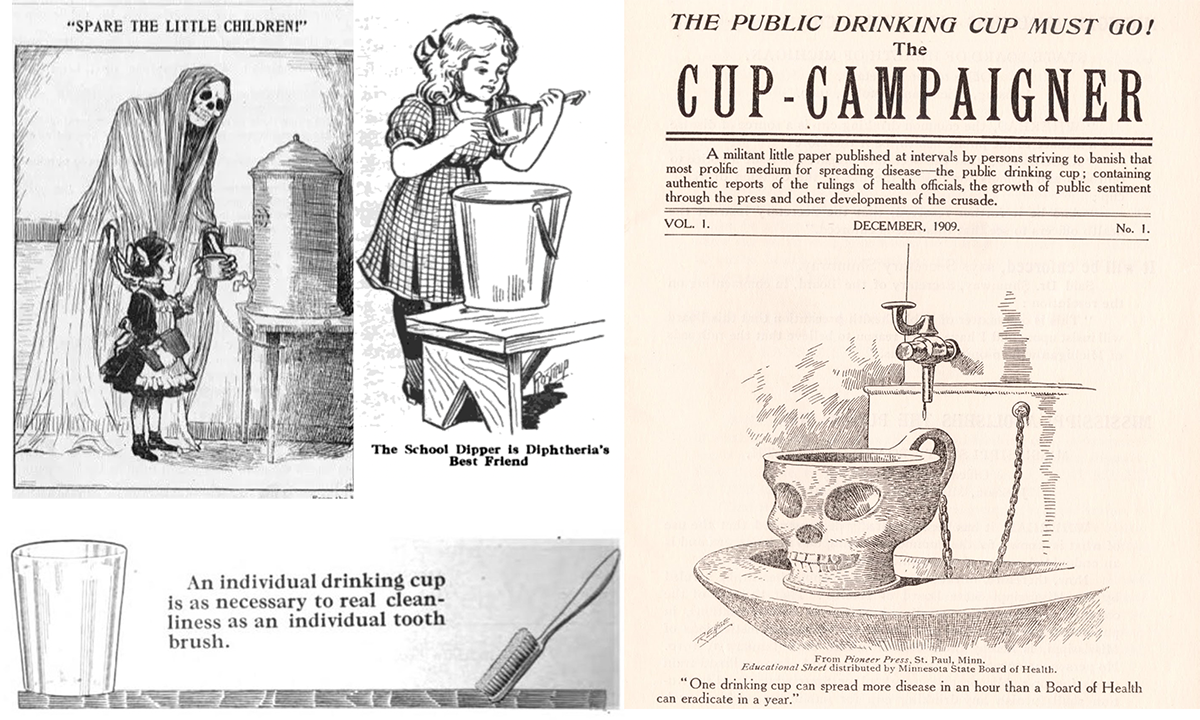

Through the early twentieth century, a communal cup was commonly used in public and private settings. In 1912, only six out of 31 classrooms in Gloucester’s Black schools had individual cups (Virginia Department of Education [VDE] 1914). Convincing schools to use individual cups was a major public health campaign in the 1910s due to the role the common cup played in spreading diphtheria (Figure 1). In 1915, the Virginia Department of Health (VDH) said, “Every teacher who is mindful of the health of her pupils will not only insist that they have individual drinking cups but will prescribe penalties for children who fail to bring their cups or to use them” (VDH 1915).

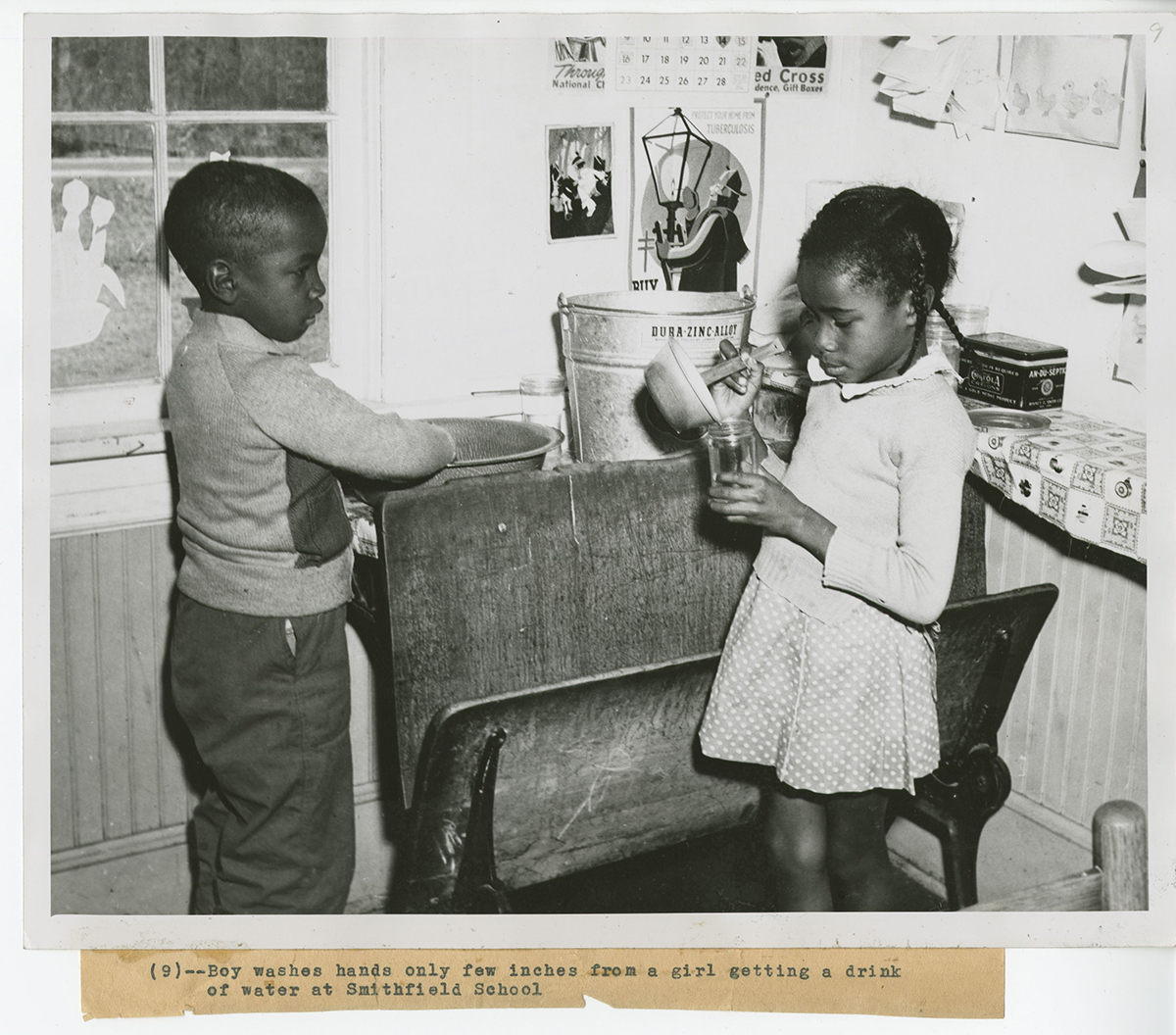

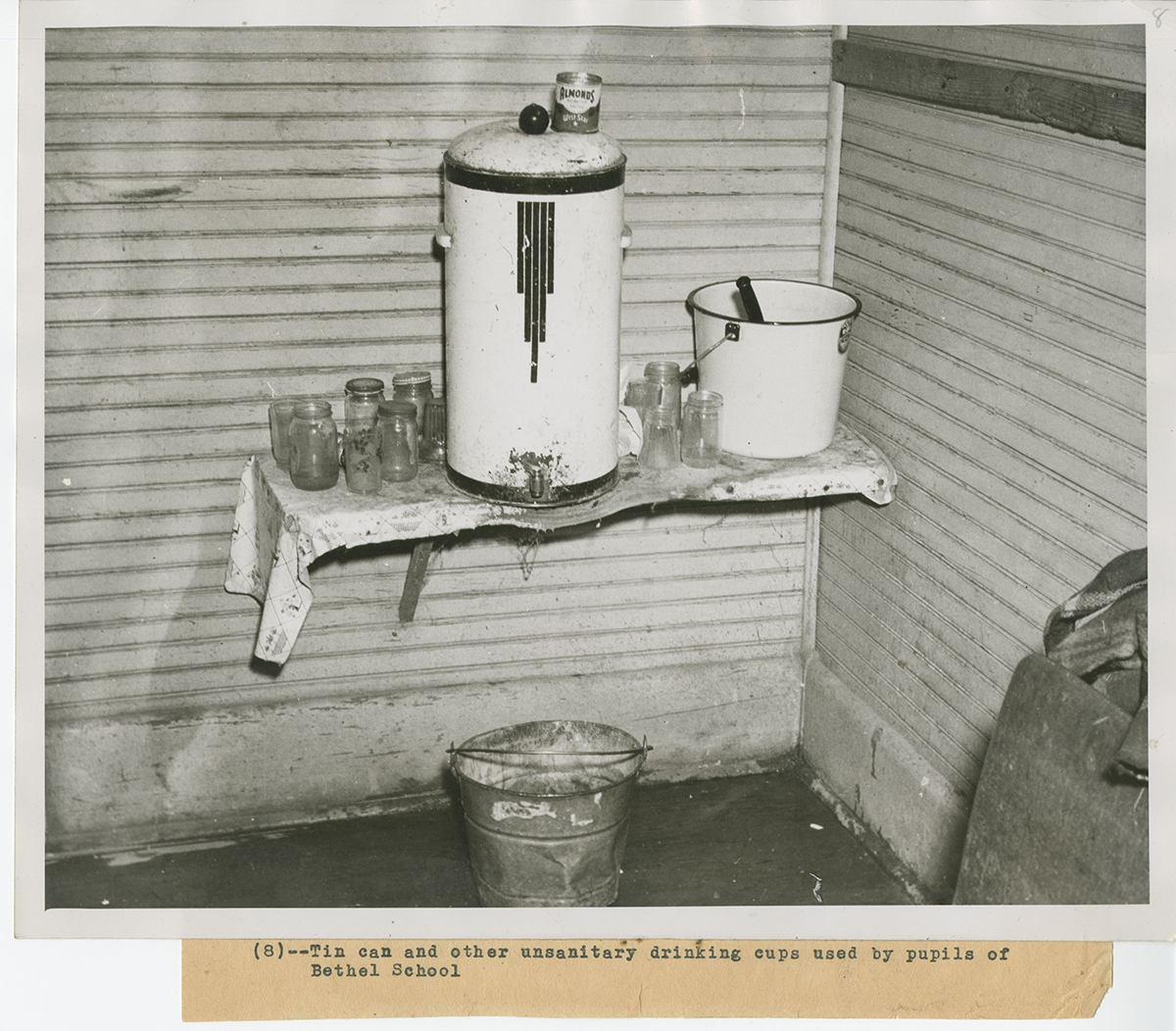

Bethel, Woodville, and Glenns/Dragon Schools never had running water. This was usual in the nineteenth century, but by the 1920s most white elementary schools in Gloucester had running water (Gloucester County School Board [GCSB] 1922–1934, 1934–1947). At Glenns/Dragon, a stream and spring were the main water source. At Woodville, it was a pump. Water at Bethel at times came from a pump, but by 1940 it was broken, and water was being obtained from a spring directly under the boy’s privy. A well was dug at Bethel in 1948 as part of a NAACP lawsuit requiring improvements (GCSB 1947–1959). Water was kept in a bucket and poured with a dipper or placed in a water cooler (Figure 3). Students used jars, glasses, and even tin cans to drink (Figure 4).

The large number of jelly juice jars and other drinking glasses found in the 1886–1923 midden at Woodville suggests that they were two of the six classrooms with individual cups mentioned in the 1912 VDE report on school conditions. No jelly jars or other tumblers were found at Glenns/Dragon (1883–1929) suggesting that the school may never have had individual glasses. A ceramic mug handle could be from communal drinking cup, or students may have used their hands or drank from a communal dipper. The wide variety of jelly jar and tumblers, colors, and decorations from Bethel (1923–1951) suggests that every child had their own cup (Figure 5). Individual drinking cups required community buy-in as cups had to be brought by students and were not provided by the school. By the time Bethel closed in 1951, individual cups had been normalized. In fact, drinking cups in schools were being condemned as unsanitary and water fountains were seen as healthier. The use of drinking cups and spring water were used as evidence for racial discrimination in Gloucester schools in the successful 1947–1949 NAACP lawsuit against the GCSB noted above (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

The archaeology at these three African American Gloucester schools shows the impact of the individual cup campaign on daily life, how healthier practices were not adopted universally across all schools, and how health concerns shifted over time. This is especially true in Black schools where health concerns kept modernizing, but schools did not due to racial discrimination. It finally took legal action to improve the drinking water situation at Bethel. As seen through the jelly juice jars, the communal cup campaign was only one of many community health efforts in schools. Schoolhouses were places where the government could reach children living in remote areas which made them ideal places to focus these campaigns. The focus of the campaign against common cups in schools helped lead to its success, socializing children into the understanding that sharing cups was bad, which they helped share with the wider community and passed on to their children, creating the now almost universally shared belief that the individual cup is sanitary and the communal cup is dirty. Jelly juice jars are just one example of how schoolhouse sites can be used to examine larger social movements, such as those related to public health and Civil Rights.

Figure 1: Jelly Juice Jar Fragments from the Woodville School. Note the bands of knurling in various patterns, including circles on the fragment in the upper right.

Figure 2: National and Virginia-based Ads Against the Communal Cup. Left to right: The Cup-Campaigner (1910), VDH (1912a), The Cup Campaigner (1909), Bottom: VDH (1912b).

Figure 3: 1948 Photo of Students Getting Water at the Smithfield School in Gloucester County, Virginia. Evidence photo from the NAACP lawsuit against the GCSB. Original caption stated: “(9) – Boy washes hands only few inches from a girl getting a drink of water at Smithfield School.”

Figure 4: 1948 Photo of the Water Cooler and Drinking Vessels at Bethel School. Evidence photo from the NAACP lawsuit against the GCSB. Original caption stated: “(8) – Tin can and other unsanitary drinking cups used by pupils of Bethel School.”

Figure 5: Jelly Juice Jar and Depression Glass Tumbler Fragments from the Bethel School. Note the colorless, pink, and green fragments.

References

Bowditch, Barbara

1986 American Jelly Glasses: A Collector’s Notebook. B&G Bowditch, Rochester, New York.

Gloucester County School Board

1922–1934 Minute Book. Gloucester County School Board, Roanes, Virginia.

1934–1947 Minute Book. Gloucester County School Board, Roanes, Virginia.

1947–1959 Minute Book. Gloucester County School Board, Roanes, Virginia

National Archives

1948 Alice Lorraine Ashley, et al. v. School Board of Gloucester Co. and J. Walter Kenny, Division Superintendent. Electronic document, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/81144802, accessed January 2023.

The Cup-Campaigner

1909 “One drinking cup can spread more disease in an hour than a Board of Health can eradicate in a year.” The Cup Campaigner I(1):1.

1910 “Spare the Little Children.” The Cup-Campaigner I(2):1.

Virginia Department of Education

1914 Virginia School Report: Annual Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the Commonwealth of Virginia with Accompanying Documents School Year 1911-1912. Davis Bottom, Superintendent of Public Printing, Richmond, Virginia.

Virginia Department of Health

1912a Diphtheria: The White Terror of Childhood. Virginia Health Bulletin IV(10):5–31.

1912b Virginia Health Almanac. Virginia Health Bulletin IV(1–2):223–262

1915 The Sanitary School and What It Means to the Public Health Second Edition. Virginia Health Bulletin VII(10):341–364.