Featured Fragment – Showing Irish Pride in Nineteenth Century Washington, D.C.

By Lauren McMillan, Ph.D.

For this month’s blog we have a guest author, Dr. Lauren McMillan, Assistant Professor at the University of Mary Washington and noted pipe researcher. She is going to discuss the ‘Home Rule’ tobacco pipe bowl recovered by Dovetail during a 2017 excavation in Washington, D.C.

Tobacco use and its meanings in North America have evolved over the past 3,000+ years from ingestion as a religious act in the prehistoric period to the secular and habitual in the colonial and post-colonial eras. Today, smoking has a contested social meaning due to our understanding of the health risks involved with smoking, but also through a renewed (or continued) recognition among some Native American groups of the sacred nature of tobacco (Rafferty and Mann 2004; Snyder 2016). Until relatively recently, the primary way tobacco was ingested was via pipes of various forms. By the mid- to late-seventeenth century, smoking had become ubiquitous among all levels of society (Photo 1).

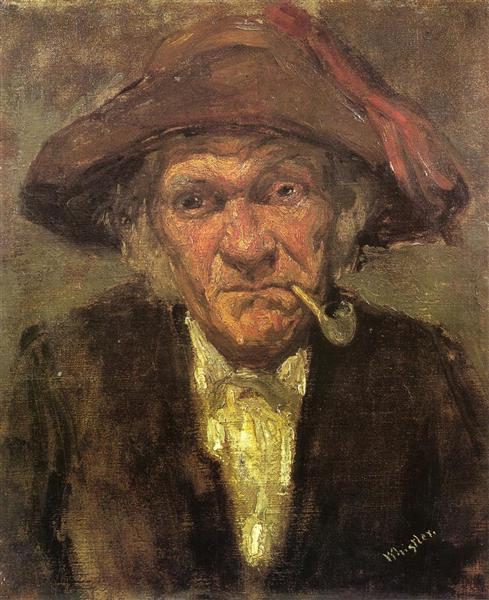

However, in the nineteenth century, pipe smoking was often associated with members of the working class (Photo 2), particularly the use of short stemmed, or “cutty,” pipes as this style of pipe could be held in the mouth by the lips alone, leaving one’s hands free to perform various tasks (Cook 1989; Fox 2016).

The pipe recovered by Dovetail in Washington, D.C.—the subject of this blog post—was stamped with a harp, clover sprigs, and the motto “Home Rule.” This type of pipe would have been mass produced in Europe and imported into the United States in the late-nineteenth century.

The Home Rule movement started in Ireland in 1870 and represented Irish independence from British Rule; this movement continued into the first two decades of the twentieth century until the passage of the Fourth Irish Home Rule Act in 1920 which gave full independence to Northern Ireland and partial rule in Southern Ireland (McCaffrey 1995). Knowledge of the Home Rule movement made its way to the United States in the late 1870s and became a prominent social and political ideology among Irish immigrants, providing a common rallying point and community bond for newly transplanted groups of people (Reckner 2001).

Clay tobacco pipes with Irish imagery of all sorts (harps, clovers, “Home Rule,” and “Erin Go Bragh”) have been recovered from archaeological sites throughout the United States, from the East Coast to the West Coast (Pheiffer 2006), but most notably in large cities in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic where there were large Irish neighborhoods in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. While these pipes can be used to easily identify the ethnicity of the people archaeologists are studying (“Irish people smoked pipes with Irish imagery”), they can also be used to form a more nuanced understanding of the social and political environment of late-nineteenth-century America. Paul Reckner (2001, 2004), in his research into political imagery on pipes recovered from Irish neighborhoods in New York and New Jersey, argues that people were purchasing and using these pipes as a way to not only demonstrate pride in their homeland, but also as a way to reject and resist nativist, anti-Irish rhetoric.

Beyond the obvious and explicit imagery on this pipe (“Home Rule,” harp, and clover), the placement of the motto and motifs also have meaning (McMillan 2015). These symbols were placed on the back of the bowl of the pipe, facing the smoker and not the outside world; this implies that the intended audience of the imagery was the smoker themself, not other people. Every time the smoker took a drag from the pipe, they would be face to face with these words and images. These symbols would have served to remind the smoker of their homeland, their political stances, and their place within a larger Irish community during a time when the Irish (and other immigrant populations) were facing discrimination and oppression in their new country. Might they have taken comfort and a renewed sense of purpose from not only the tobacco they were ingesting, but also the powerful and meaningful images placed on the pipe?

So, while you are celebrating St. Patrick’s Day this year (if you partake), think of people of Irish decent over the past several centuries who embraced Irish imagery daily as a reminder of their heritage, not just once a year.

For more information and images please visit

https://www.jefpat.org/CuratorsChoiceArchive/2013CuratorsChoice/Mar2013-ErinGoBragh-TobaccoPipesAndIrelandsStruggleForIndependence.html

Any distributions of blog content, including text or images, should reference this blog in full citation. Data contained herein is the property of Dovetail Cultural Resource Group and its affiliates.

References:

Cook, Lauren J.

1989 Tobacco-Related Material Culture and the Construction of Working Class Culture. In Interdisciplinary Investigations of the Boott Mills, Lowell, Massachusetts, Vol. III: The Boarding House System as a Way of Life, edited by Mary C. Beaudry and Stephen A. Mrozowski, pp. 209–230. Cultural Resources Management Study, No. 21, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, North Atlantic Regional Office, Boston, Massachusetts.

Metsu, Gabriel

1663 The Old Drinker. Electronic document, https://fineartamerica.com/featured/the-old-drinker-1663-gabriel-metsu.html, accessed March 2018.

Fox, Georgia L.

2016 The Archaeology of Smoking and Tobacco. The University of Press of Florida, Gainsville.

McCaffrey, Lawrence J.

1995 The Irish Question: Two Centuries of Conflict. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington.

McMillan, Lauren K.

2015 Community Formation and the Development of a British-Atlantic Identity in the Chesapeake: An Archaeological and Historical Study of the Tobacco Pipe Trade in the Potomac River Valley ca. 1630–1730. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Pheiffer, Michael A.

2006 Clay Tobacco Pipes and the Fur Trade of the Pacific Northwest and Northern Plains. Phyolith Press, Ponca City, Oklahoma.

Rafferty, Sean M., and Rob Mann

2004 Introduction. In Smoking and Culture: The Archaeology of Tobacco Pipes in Eastern North American, edited by Sean M. Rafferty and Robb Mann, pp. xi–xx. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Reckner, Paul E.

2001 Negotiating Patriotism at the Five Points: Clay Tobacco Pipes and Patriotic Imagery among Trade Unionists and Nativists in a Nineteenth-Century New York Neighborhood. Historical Archaeology 35(3):103–114.

2004 Home Rulers, Red Hands, and Radical Journalists: Clay Pipes and the Negotiation of Working-Class Irish/Irish American Identity in Late-Nineteenth-Century Paterson, New Jersey. In Smoking and Culture: The Archaeology of Tobacco Pipes in Eastern North America, edited by Sean M. Rafferty and Rob Mann, pp. 241–271. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Snyder, Charles M.

2016 Restoring Traditional Tobacco Knowledge: Health Implications and Risk Factors of Tobacco Use and Nicotine Addiction. In Perspective on the Archaeology of Pipes, Tobacco and other Smoke plants in the Ancient Americas, edited by Elizabeth A. Bollwerk and Shannon Tushingham, pp. 183–198. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland.

McNeill Whistler, James

1859 Man Smoking a Pipe, circa 1859. Electronic document, https://www.wikiart.org/en/james-mcneill-whistler/man-smoking-a-pipe, accessed March 2018.

Highmore, Joseph

1735–1745 Mr. Oldham and His Guests. Electronic document, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/highmore-mr-oldham-and-his-guests-n05864, accessed March 2018.